Excerpt from the Report of the Working Group on an A2JBC Family Justice Leadership Strategy (November 2020).

Brain science, ACEs and resilience research and the family justice system

The scientific evidence

As has been done in other sectors, the justice sector needs to root its understanding of child and family well-being in the scientific evidence. Brain science tells us that the healthy development of children’s brains is a crucial determinant of future well-being. Non-stressful interaction with loving adults enhances healthy brain development. Trauma and toxic stress interfere with it.

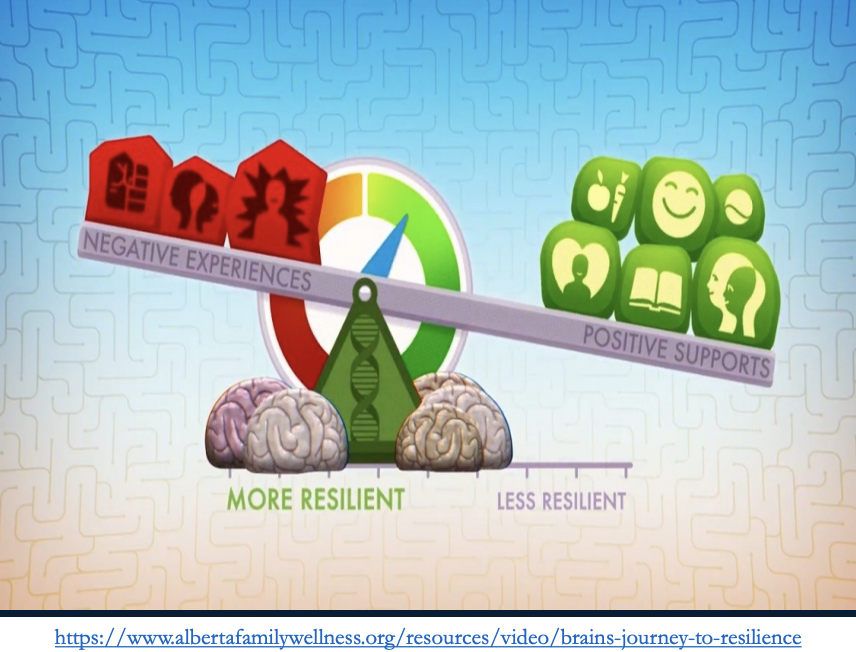

The research on Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs) identifies ten childhood experiences that potentially create toxic stress and risk negative immediate, long-term and intergenerational impacts. (See Figure 3, ACEs chart.) Divorce and parental separation is an ACE, as are other family justice related issues such as child neglect (physical and emotional) and abuse (physical, emotional, sexual), and household dysfunction including mental illness, substance abuse violence and incarceration.

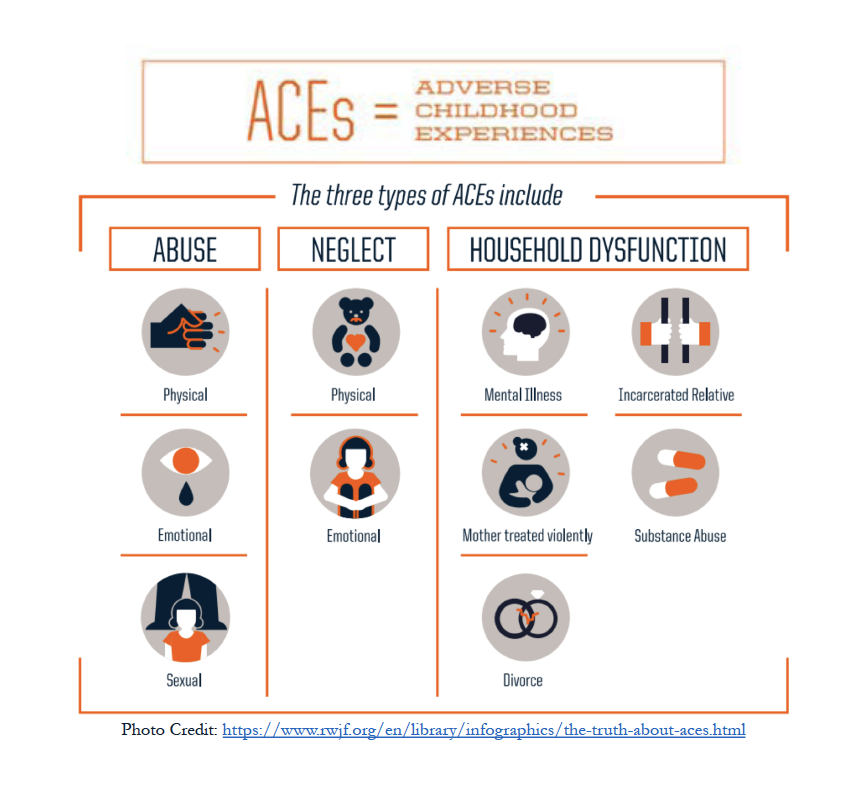

The more ACEs experienced by children, the higher the risks of immediate and future negative outcomes. The presence of adverse social conditions and historical trauma also increase risks and lead to intergenerational impacts. (See Figure 4 Pyramid of ACEs Context and Impacts.)

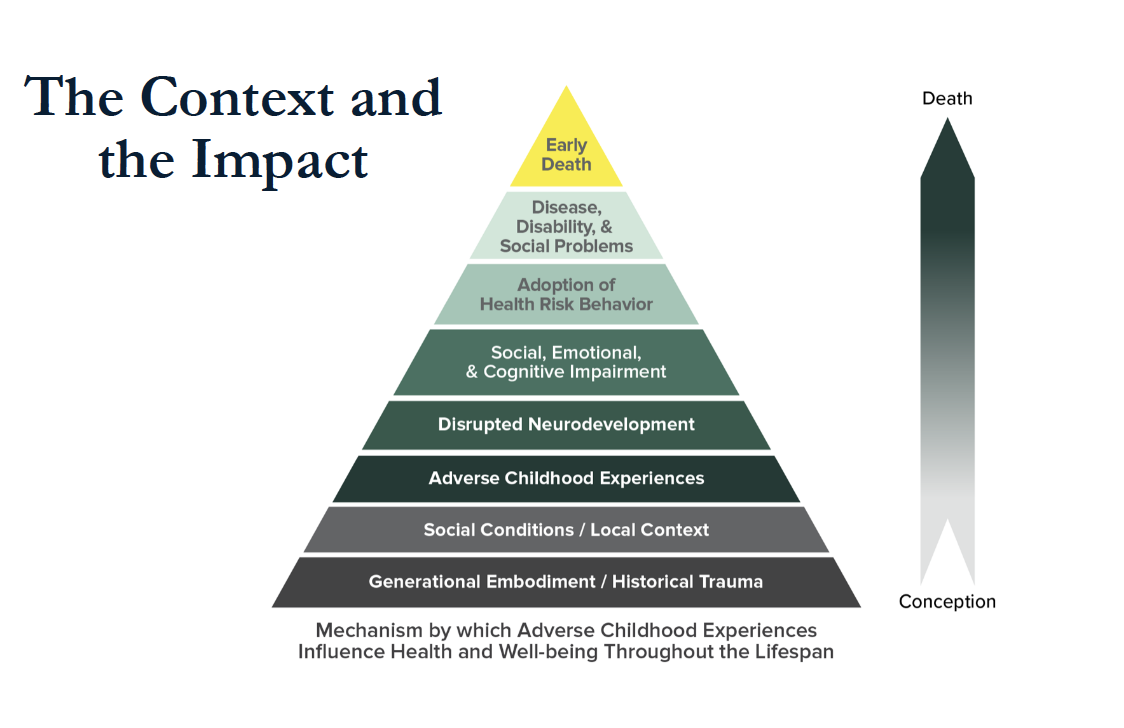

But the news is not all bad. Resilience, inherent in all of us and strengthened through healthy brain development, helps with the management of stress. There is something that can be done to ameliorate the negative impact of ACEs: negative experiences can be reduced, resilience strengthened and positive supports provided. (See Figure 5, Resilience Scale.)

While the biggest potential impact of toxic stress is on the brains of young children and adolescents, adults (especially those who themselves have experienced multiple ACEs) continue to be undermined by toxic stress experienced in adulthood. Their resilience can also be strengthened, albeit not as easily as the resilience of children and youth. With a non-stressful environment and the right supports, adults who have themselves experienced ACEs can provide the necessary stability to their children when those children are experiencing adversity, so that the stress is not toxic and the child’s resilience is strengthened rather than undermined.

Figure 3: Adverse Childhood Experiences

Figure 4: Pyramid of ACEs context and impacts

How does this play out in the family justice system?

Differences among family members are inevitable, and are not necessarily harmful to children. Experiencing some level of stress is what strengthens children’s resilience. If the differences are managed well within the family, children develop the capacity to manage conflict well as adults.

It is when families are having difficulties managing differences that they often come into contact with the family justice system. Families facing family justice issues related to separation and divorce, such as, neglect and abuse and family dysfunction, including mental health and substance abuse, violence and incarceration (all designated as ACEs) will likely be experiencing heightened stress that could be or become toxic.

The family justice system is intended to help families resolve disputes about their family justice issues. In practice, however, the system often exacerbates the stress families are already experiencing, thereby increasing the likelihood that the stress will become toxic.

This is, in part, because the family justice system is based on an adversarial dispute resolution model. In this model, the justice system’s role is to provide a neutral third-party decision-making process for unresolved disputes. The adversarial model assumes that the best way for that neutral third party to make just decisions is in a court process that regulates a clash between opposing forces. It is presumed that out of this clash will emerge justice.

While the system may see itself as playing the benign role of helping to resolve disputes, the adversarial approach creates a win/lose narrative that fuels, rather than diffusing, the toxic stress that may be at play in the conflict between the adults in the family. From the perspective of the participating adversaries, the system encourages them to dredge out the most negative aspect of the other, assume the worst at each stage, confront the other, and work towards an end goal of overcoming the other. Rather than creating optimum conditions for an environment that supports healthy brain development in children, it increases the toxic stress and risks serious immediate, long-term and intergenerational negative health effects on both children and adults.

What is the family justice system’s role in promoting family well-being?

“To be entirely or even mainly focused on the resolution of disputes in our pursuit of justice is, I submit, to miss much that we should expect of our legal systems. A broader view is needed.”

- Richard Susskind, Online Courts and the Future of the Justice System, p. 66

Richard Susskind argues that the concept of access to justice should embrace four elements:

- Dispute resolution – an authoritative forum for the vindication of people’s legal rights

- Dispute containment – nipping disputes in the bud or providing justice system responses that are proportionate to what is at stake and in the best interests of litigants

- Dispute avoidance - building a fence at the top of the cliff, rather than focusing on how responsive and well-equipped the ambulance is at the bottom

- Legal health promotion – empowering people to access the many benefits that the law can confer.

We can deduce from the brain science that adversarial dispute resolution processes, designed as clashes between the participants, should, as much as possible, be avoided to the benefit of all family members, particularly the children. A family justice system focused on family wellbeing will lead to designing a system that creates the conditions for de-escalation of conflict, and puts a premium on the dispute containment and avoidance roles of the family justice system. This might mean using the authority of judges to divert cases out of the justice system entirely, or creating a presumption of consensual dispute resolution (including mediation and Collaborative Practice, such as is currently being tested by the BC Provincial Court in Victoria, and soon Surrey), or working upstream to avoid court entirely.

Promoting legal health includes empowering family members to manage their own conflicts and to live a good life, in accordance with their rights as humans, as Indigenous peoples or as children. This might mean providing separating parents easy access to online co-parenting tools or child support calculators, or involving Elders in decisions about the children from their communities, or giving children and youth the safe opportunity to participate in decisions that impact them, and thereby allowing them to realize their rights under the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child.

Focusing the family justice system on family well-being and taking a broader view of access to justice will lead to policies and programs that we have only begun to imagine.

Working in partnership with other sectors

From the perspective of the family (adults, youth and children), family legal issues are most often secondary to social, relationship, parenting and financial issues. Making family well-being the focus of the family justice system leads to recognizing that the justice sector is not where the solutions lie for most families. The authority of the court may still be needed to combat power abuses within families, but issues that require skills, knowledge and experience not held by judges and lawyers can and should be referred to others outside the justice system.

A transformed family justice system focused on family well-being will support and be supported by professionals from other sectors, and all will be aligned around the common goal of child and family well-being. The justice sector will be integrated with the health (particularly mental health), education and social services sectors, allowing lawyers, judges and mediators to do what they do best, but not in a silo that plays down the non-legal issues of families.

The shift in focus to family well-being is not intended to turn lawyers and judges into social workers or mental health professionals. Instead, it will lead to the justice system working alongside other societal systems, and together with them, supporting families to achieve wellbeing by offering its particular contribution to that goal.

While the health and social services sectors may be seen as the more obvious leads in generally promoting family well-being, it is up to the justice system to take the lead in designing justice sector policies and processes, and supporting innovations, that reduce toxic stress, strengthen resilience and get families the support they need as they work through multi-faceted issues that bring them into contact with the family justice system.