Report of the Working Group on an A2JBC Family Justice Leadership Strategy (November 2020)

Access to justice is not just about process, it is about creating the conditions that allow people to live a good life. In the family justice system, improving access to justice means designing a system that promotes family well-being.

In October 2019, the Access to Justice BC (A2JBC) Leadership Group committed to addressing the negative impacts on child well-being when families are interacting with the family justice system. It directed that a “practical” leadership plan be developed for A2JBC to meet this commitment. This report represents the deliberations of a working group (see Appendix 2) set up to assist with that direction. It makes recommendations for the first phase of an A2JBC leadership plan.

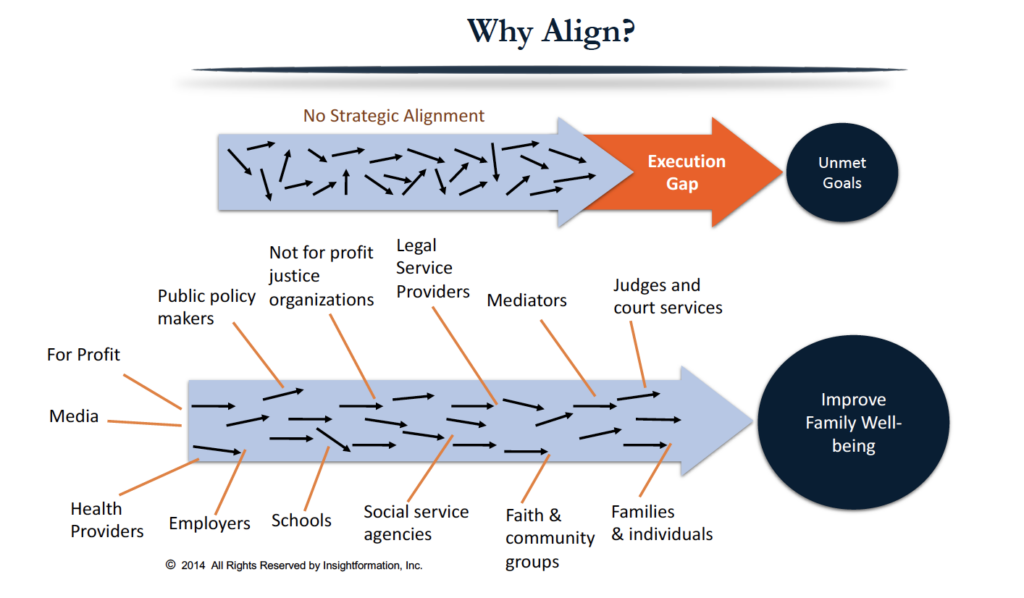

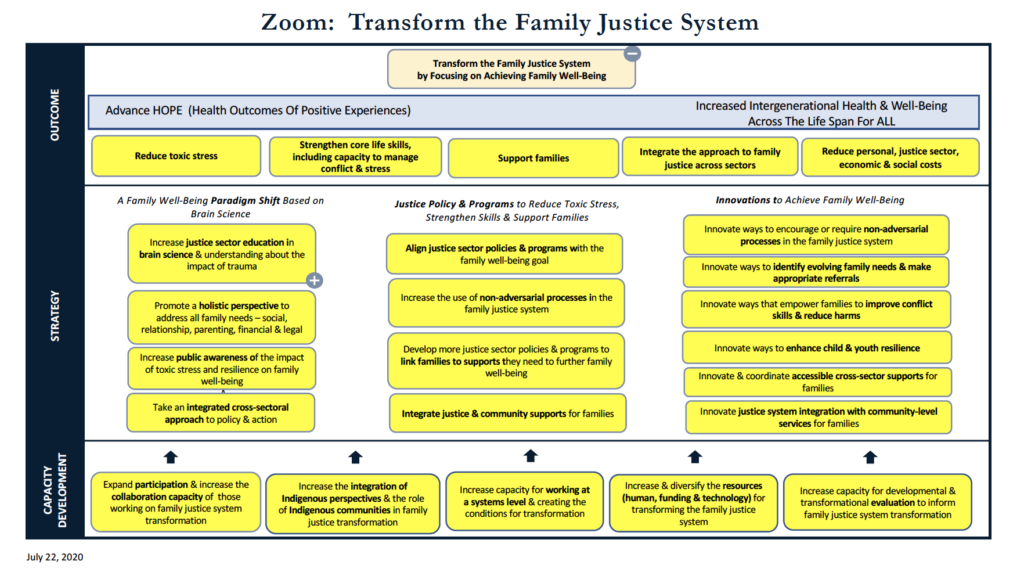

The report recommends that A2JBC lead a collaborative directed at transforming the family justice system by focusing on family well-being. The ‘Transform the Family Justice System’ (TFJS) Collaborative will coordinate the efforts of the many organizations and individuals (both in the justice sector and across other sectors) needed to make this transformation happen. It will take an approach known in the tech world as “highly aligned, loosely coupled”, and encourage innovative activities at both the community and provincial level, and integration with family-focused policies and programs in other sectors.

Vision: a family justice system that, together with other societal systems, supports children, youth and families

Goal: child, youth and family well-being

Figure 1: Family Justice Paradigm Shift

The road to transformation of the family justice system starts with a shift away from concentrating on the system itself, to making child and family well-being the focus - the North Star that guides decision-making along the way. This paradigm shift leads to understanding the family justice system as part of a larger supportive ecosystem involving health, education and other societal systems, and provincial and community actors outside the justice system.

The TFJS Collaborative will ground itself in the established scientific evidence about healthy brain development, Adverse Childhood Experiences and resilience. Families dealing with family justice issues often experience toxic levels of stress that have an immediate adverse health impact on all family members and risk long-term negative consequences, particularly for the children. The adversarial paradigm, upon which the court system is based, tends to exacerbate this stress. The good news is that something can be done to ameliorate the negative impacts: the toxic stress can be reduced; the resilience of children and adults can be strengthened, and family members can be supported through family transitions and stressful family situations.

Transforming the family justice system by focusing it on family well-being requires the justice sector to reach out to families, youth and children, and individuals and organizations from other disciplines and sectors, both for a better understanding of family well-being and trauma, and to partner in developing solutions that will work for families.

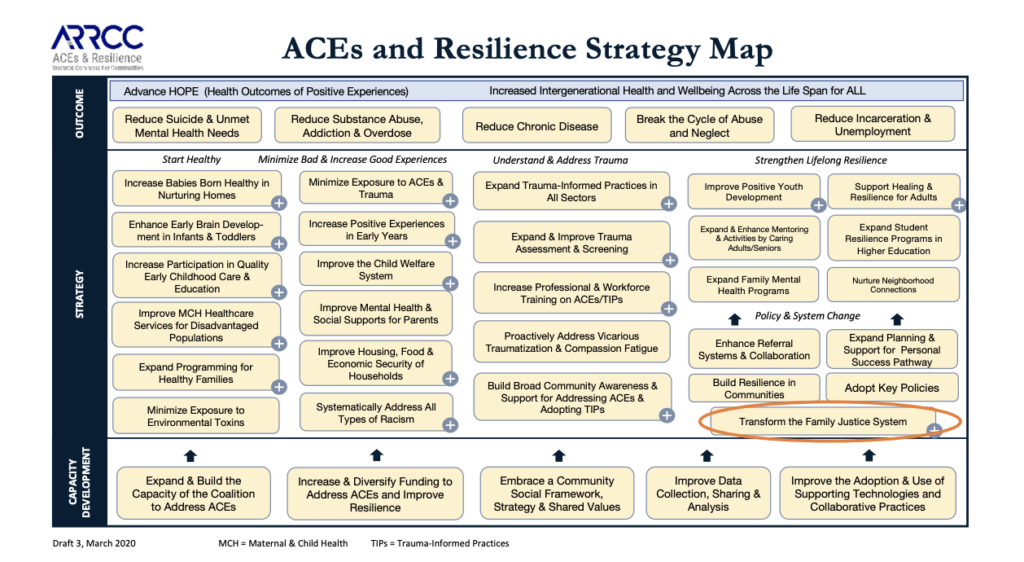

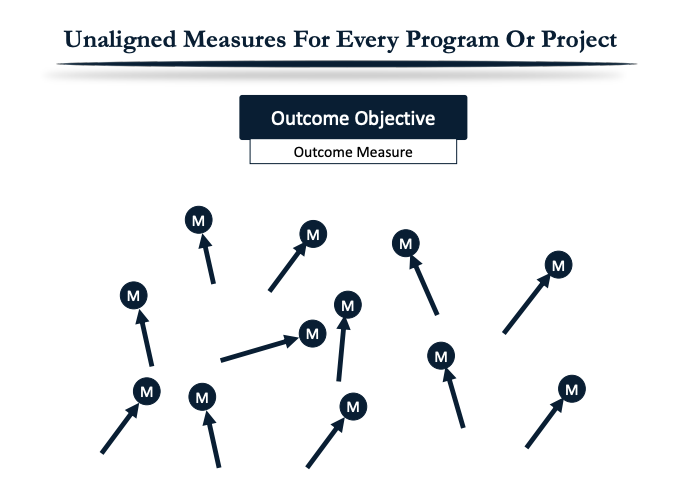

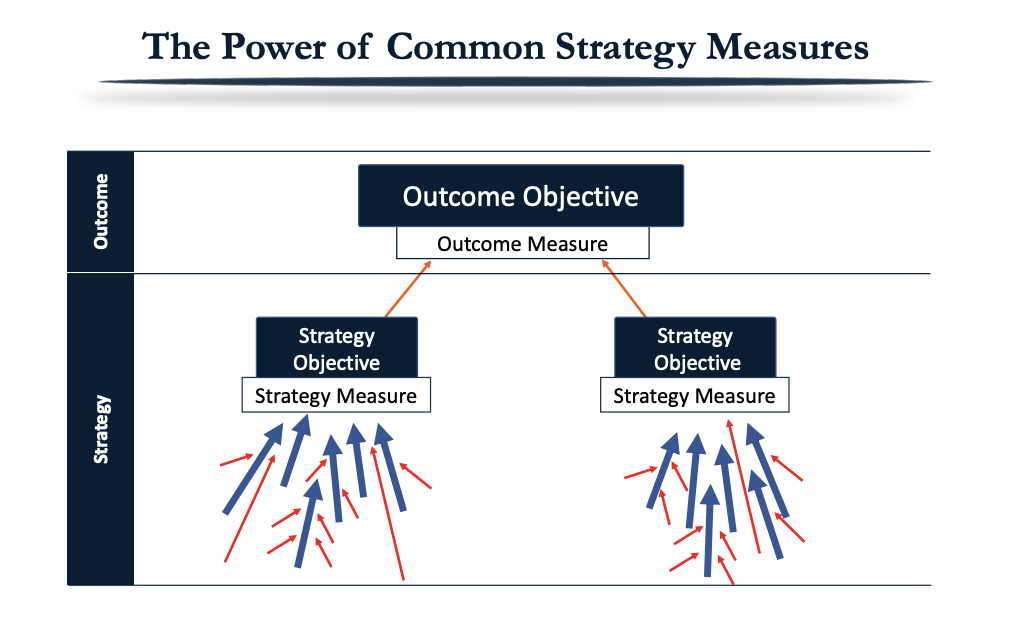

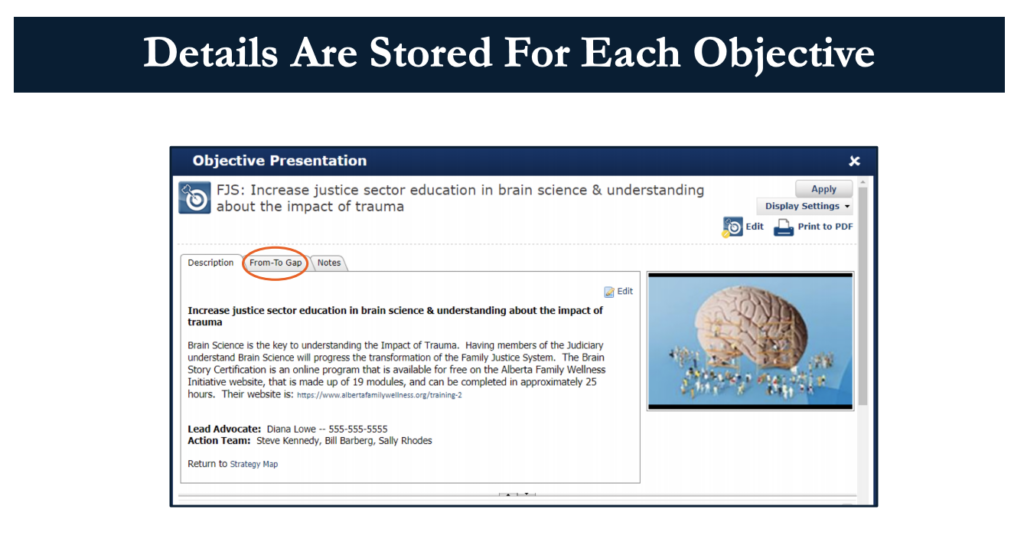

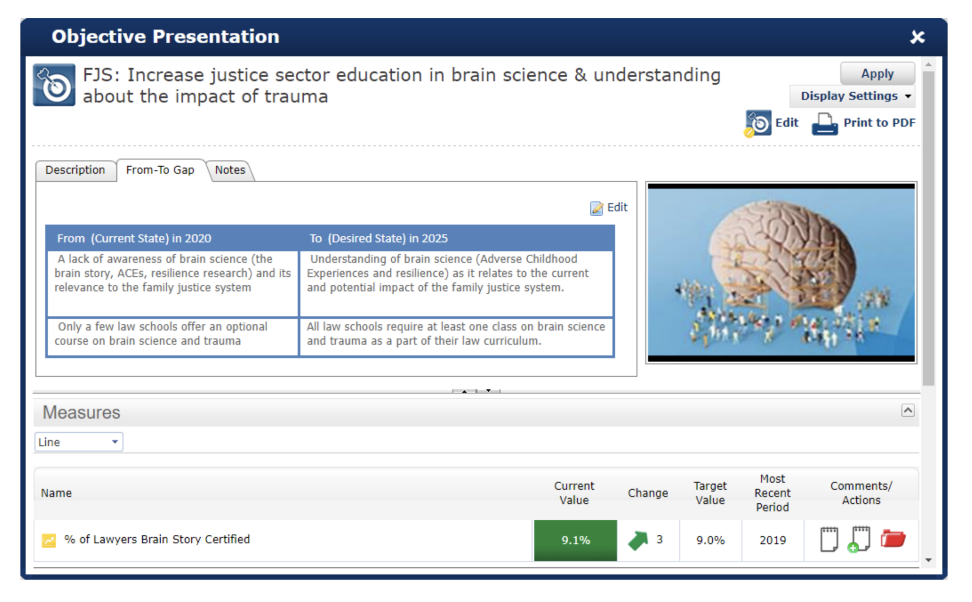

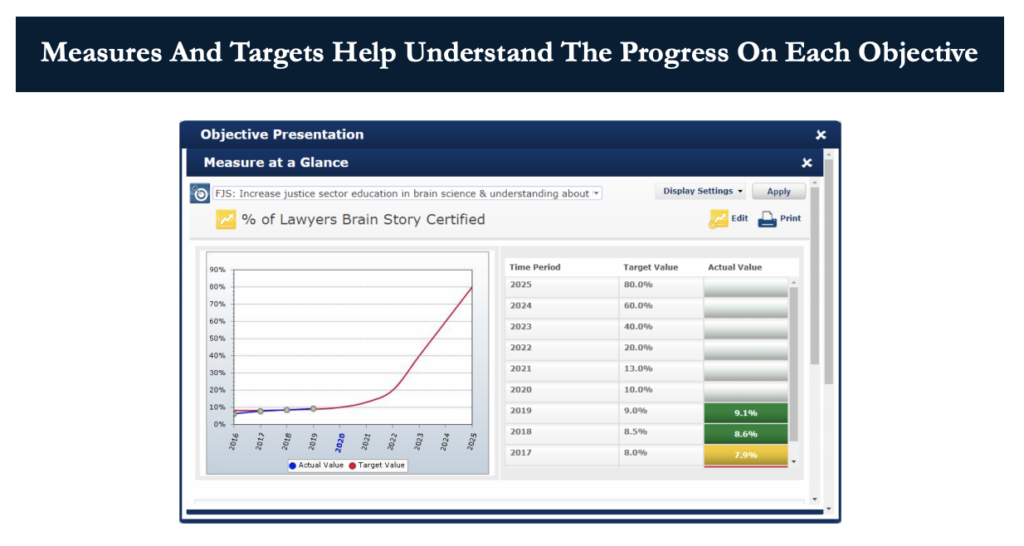

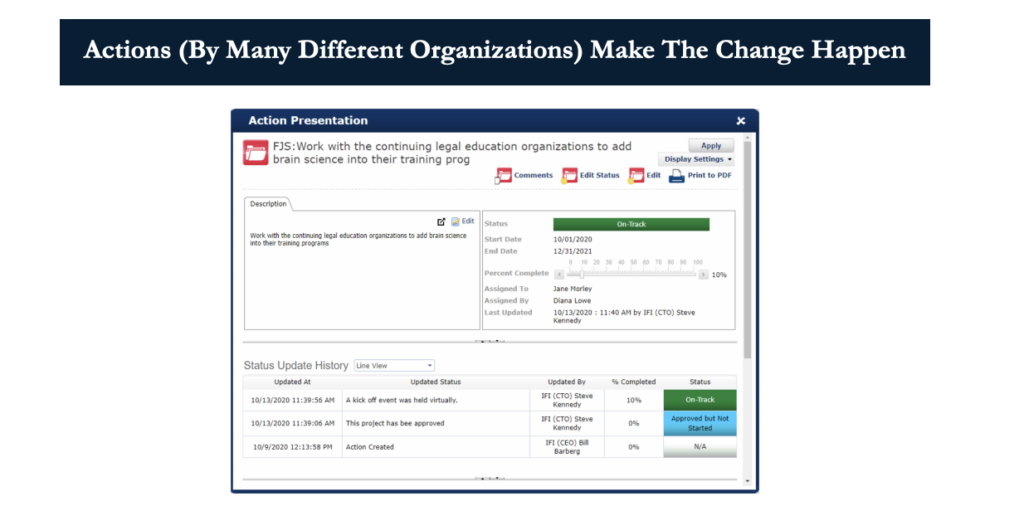

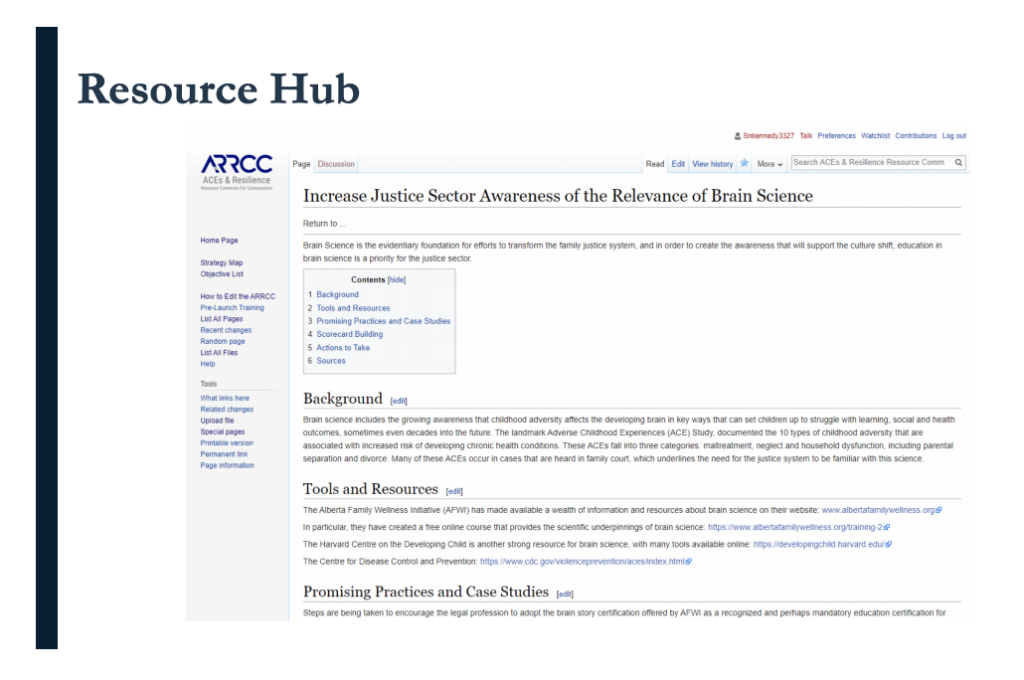

The journey towards transforming the family justice system has already begun in BC. To reach the goal requires many people and organizations aligning around common strategic objectives, coordinating activities and assessing success by using shared measures. Through the use of a strategy mapping approach, the TFJS Collaborative will create the necessary framework and backbone support for this collective effort. The use of a customised strategy map (tied to an established ACEs and Resilience Strategy Map) will strengthen the TFJS Collaborative by connecting it with organizations, across many sectors, that together are pursuing the common goal of “increased intergenerational health and wellbeing across the life span for all”.

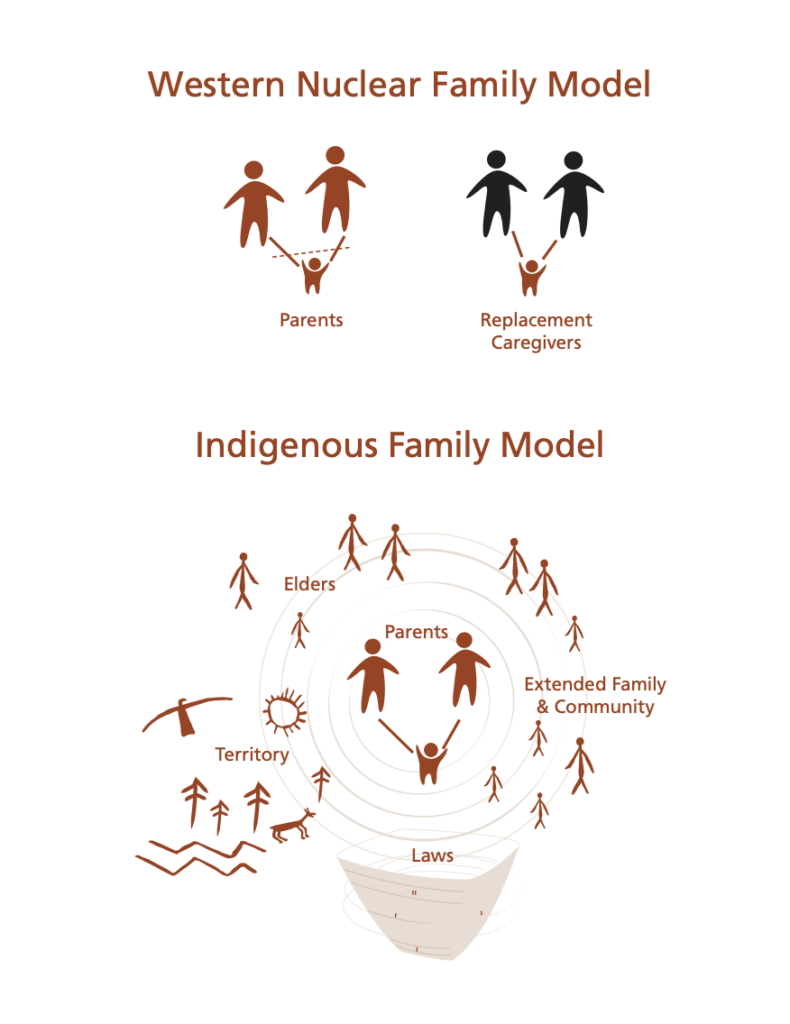

In taking this holistic approach to the family justice system, BC is fortunate to be able to learn from the traditional approaches of its Indigenous peoples. Achieving the goal of family wellbeing in the family justice system will only happen if the justice sector acts in partnership with Indigenous leaders, organizations and communities. The report recommends that A2JBC invite Indigenous leaders to co-develop, as part of the TFJS Collaborative, a strategy directed specifically at the well-being of Indigenous families in BC.

Most lawyers, judges, court workers, mediators, justice policy-makers and others working in the justice sector, value public service and experience their own stress when they know the system is not working for the people they are in it to serve. A transformed family justice system will lead to greater job satisfaction for those who work in the family justice system, which in turn will improve the services they provide.

The report sets out six specific recommendations for action by A2JBC (See Recommendations, Below):

Recommendation #1 - Announce A2JBC’s intention to create a “Transform the Family Justice System” (TFJS) Collaborative

Recommendation #2 - Re-articulate the goal, vision and overall objective of A2JBC’s October 2019 Commitment by using the language of “family well-being”, and expand the scope of the initiative to cover the entire family justice system, including separation and divorce, family violence and child protection.

Recommendation #3 - Invite Indigenous leaders to co-develop, with A2JBC in the context of the TFJS Collaborative, a strategy in sync with the BC First Nations Justice Strategy and directed specifically at transforming the family justice system for Indigenous families in BC.

Recommendation #4 - Use a strategy map framework for the TFJS Collaborative, customized for British Columbia and connected to an ACEs and Resilience Strategy Map that links the Collaborative with organizations across many sectors.

Recommendation #5 - Take immediate steps to lay the foundations for a successful TFJS Collaborative.

Recommendation #6 - Convene a “transform the family justice system” conference to launch the TFJS Collaborative, when the foundations for success have been laid.

On October 30, 2019, the Access to Justice BC (A2JBC) Leadership Group learned about

Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs), their immediate and long-term consequences, and the importance of resilience in ameliorating that negative impact. The Group reflected on the relevance of this brain science to family justice and recognized that the family justice system was contributing to serious harm being done to children. As a result, A2JBC made a Statement of Commitment (Appendix 1) to take leadership in addressing the adverse impact on children of parental conflict and anxiety during parental separation.

The Action Framework (which forms part of the Statement of Commitment) provided that “the approach to action will be collaborative (including multi-disciplinary), user-centred, experimental and evidence-based – and that an Indigenous lens will be applied.”

The first identified step was to develop a practical leadership plan to be brought back to the A2JBC Leadership Group. A working group (membership Appendix 2) was created to assist in developing this leadership plan. The working group met several times throughout 2020 to discuss strategy and review work done by A2JBC’s strategic coordinator. This is the working group’s report to the A2JBC Leadership Group.

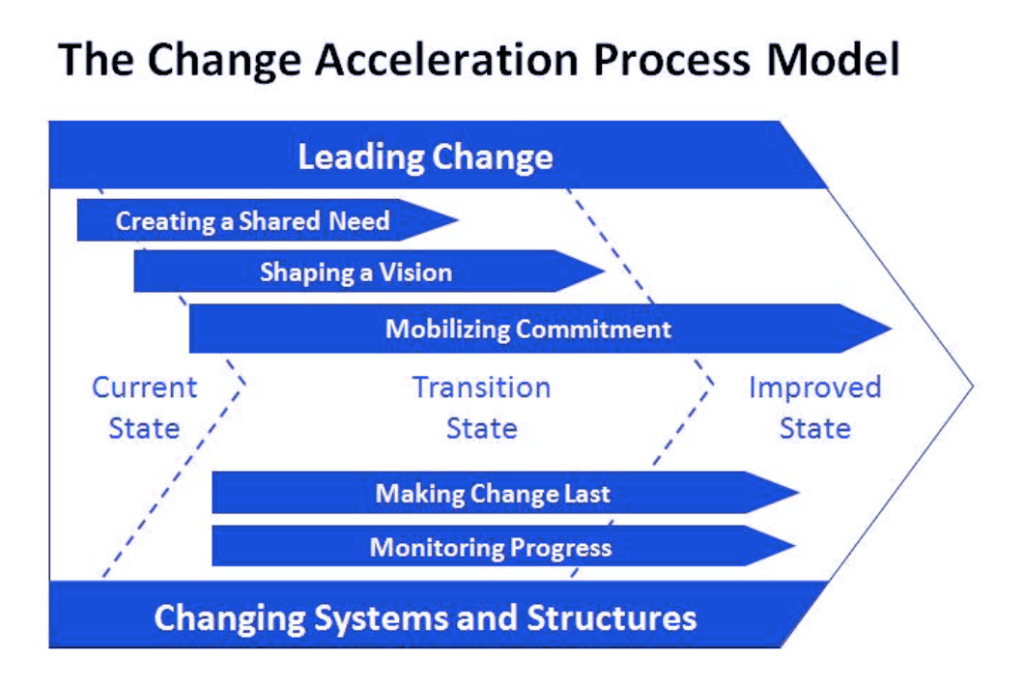

When venturing forth on an ambitious course of leadership to make a difference on a complex social issue, it is important to begin by articulating a theory of the change that it is anticipated will result from the initiative. A “Theory of Change” gives direction on a journey that by its nature will take years, not months and lead down unforeseen paths.

The following is the Theory of Change for this social impact initiative:

By focusing the design of the BC family justice system on achieving family well-being, the family justice system will be transformed and that transformation will, in turn, substantially increase the well-being of children, youth and adults experiencing family justice issues.

An A2JBC-led Family Justice Collaborative will contribute to this transformation by inspiring, strategically aligning, measuring and keeping track of activities directed at achieving family well-being through the family justice system.

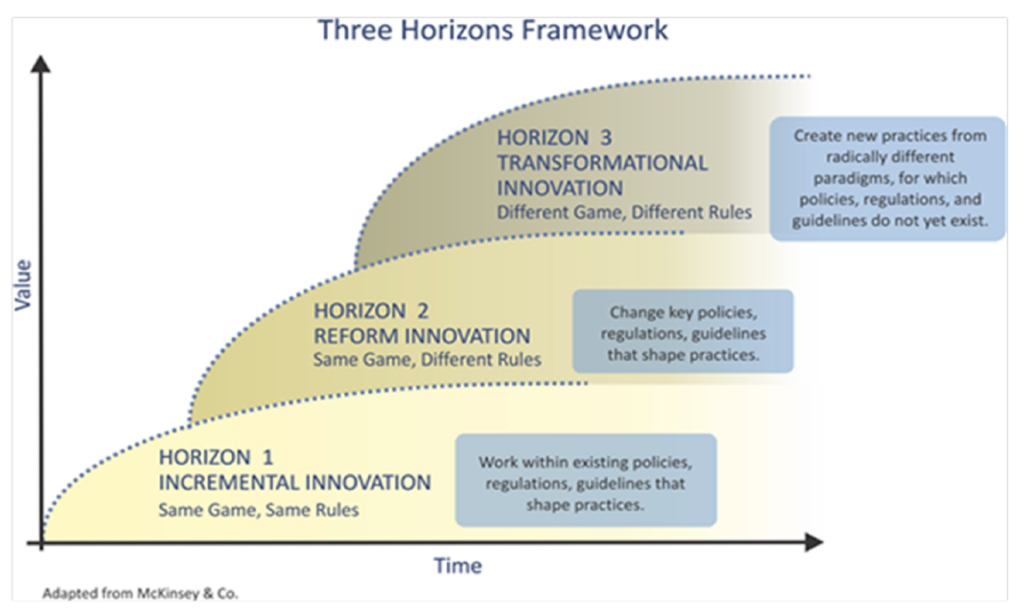

Transforming the family justice system requires pursuing the following categories of strategic objectives simultaneously:

- A paradigm shift (based on brain science, ACEs and resilience research) that looks at the family justice system from a holistic child and family perspective

- Policy and programs that reduce toxic stress, strengthen resilience, and support families, and

- Innovations involving experimenting, evaluation and scaling.

These three categories of objectives reflect the three levels of change required to sustain

systemic change – Landscape, Regime Systems and Niche Innovations – in F. Geels “Multi-level

framework on Sustainability Transitions” chart

Figure 2: Geel’s framework for system change

A2JBC is a collaborative of individuals and organizations committed to improving access to justice in British Columbia. Its mandate covers the civil and family justice system and it made an early decision to focus on family and Indigenous justice. A2JBC is well-placed to take on the leadership of the proposed TFJS Collaborative and with respect to Indigenous families, to partner with the First Nations Justice Council and others.

This is an access-to-justice issue. The harm being experienced by children, youth and families facing family justice issues is undermining family well-being and risking serious long-term and intergenerational negative consequences for children and youth. In a survey conducted by Professor Trevor Farrow and the Canadian Forum on Civil Justice, members of the public were asked how they define “justice” and “access to justice”. The researchers were surprised by the responses, which were not the typical justice system definition of “more lawyers”, “more courts”, “more judges”, “more legal aid”, or “faster time to trial”. What they found is that much of the public defined justice as “the right to a good life” (see the survey conducted by Professor Trevor Farrow and the Canadian Forum on Civil Justice at pages 970-972). Family well-being is another way of talking about the good life.

A2JBC has aligned more than 50 justice sector organizations around the Access to Justice Triple Aim. Transforming the family justice system by focusing on family well-being will further all three elements of the Access to Justice Triple Aim:

- It will improve the experience of families interacting with the family justice system.

- It will improve many aspects of access to justice at the population level.

- It will improve costs, including by saving costs in other sectors: for example, the economic costs of stress-related illnesses or of children falling back in their educational achievement.

Transforming the family justice system by focusing on family well-being will ensure that investment of public funds in the family justice system benefits children and families.

Many of the causes for the harm being done in the current situation, and the ways to ameliorate that harm, will be found outside the justice sector. Still the justice sector must take on its share of responsibility for this harm, and for developing, in partnership with others, ways of addressing it. The will to have the family justice system make a positive difference for

families must start from within the justice system.

No one justice sector organization, nor the justice sector on its own, can achieve the strategic objective to transform the family justice sector by focusing on family well-being. Collective leadership is necessary, as is a workable framework to coordinate the collective effort. A2JBC , with the necessary resources, can provide both the leadership and the framework for action.

A2JBC is only beginning to develop the justice sector’s collective leadership ‘muscle’. The proposed TFJS Collaborative will allow the sector to go beyond words of alignment. It will provide a platform for inspiring and coordinating decentralized but aligned action directed at common strategic objectives. The Collaborative and the strategy mapping framework proposed in this report will be a testing-ground and exemplar for what effective A2JBC leadership can and

should look like.

The scientific evidence

As has been done in other sectors, the justice sector needs to root its understanding of child and family well-being in the scientific evidence. Brain science tells us that the healthy development of children’s brains is a crucial determinant of future well-being. Non-stressful interaction with loving adults enhances healthy brain development. Trauma and toxic stress interfere with it.

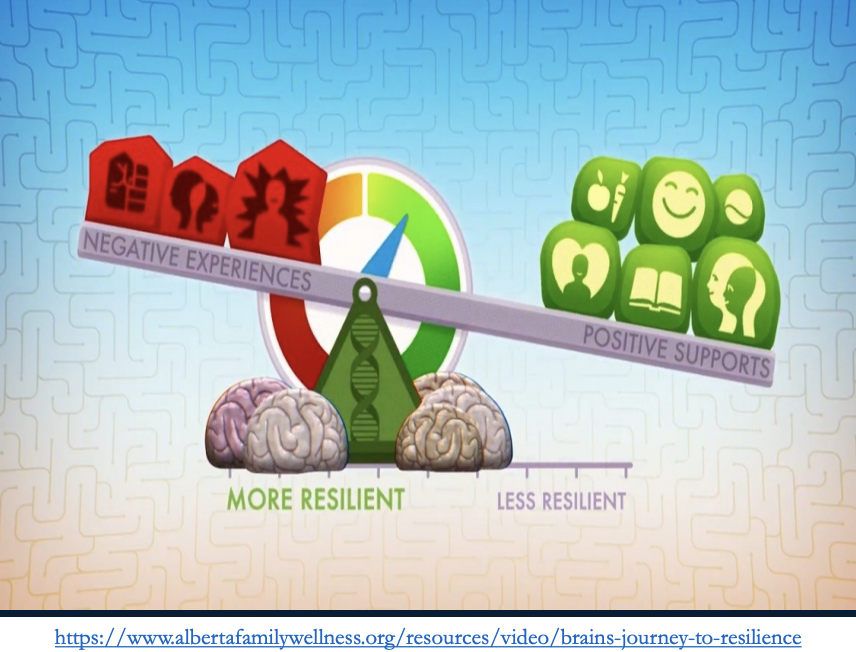

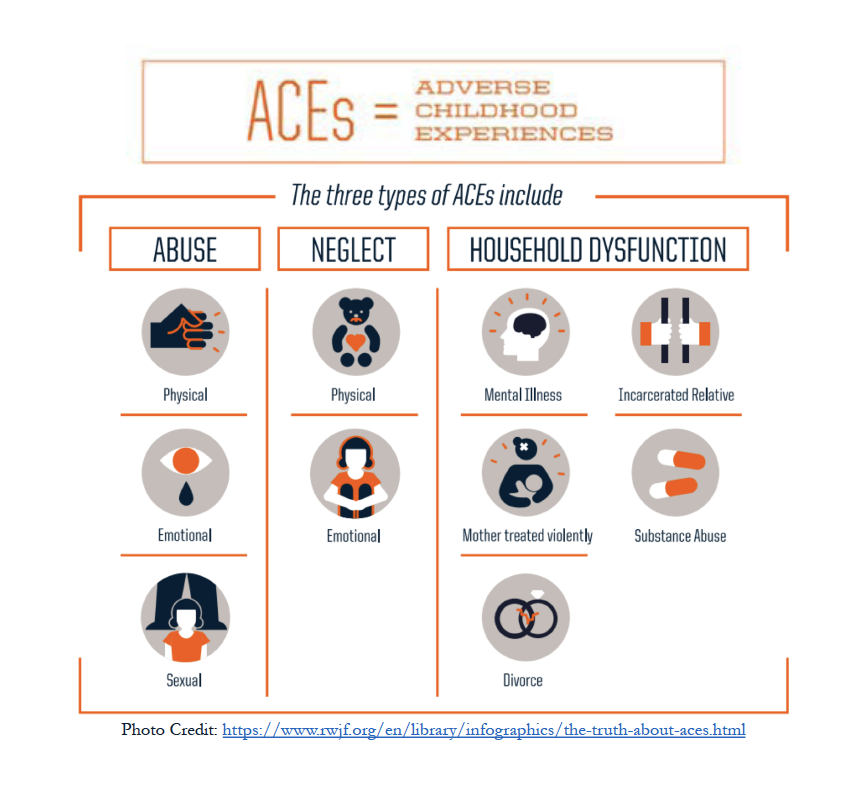

The research on Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs) identifies ten childhood experiences that potentially create toxic stress and risk negative immediate, long-term and intergenerational impacts. (See Figure 3, ACEs chart.) Divorce and parental separation is an ACE, as are other family justice related issues such as child neglect (physical and emotional) and abuse (physical, emotional, sexual), and household dysfunction including mental illness, substance abuse violence and incarceration.

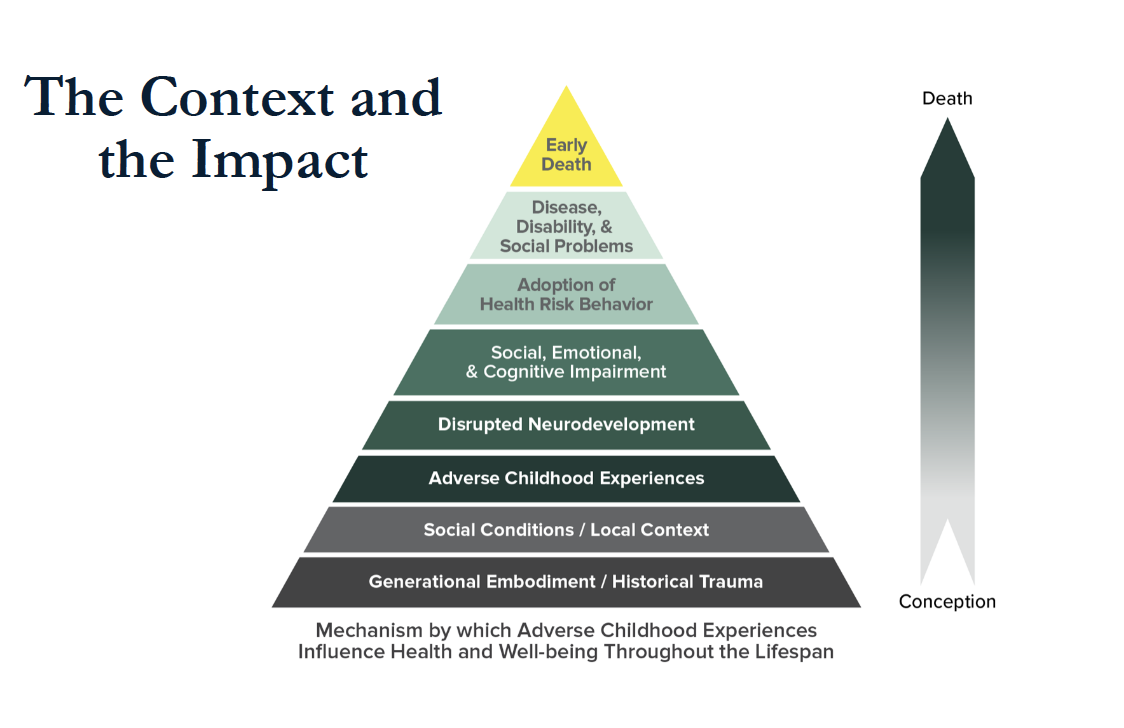

The more ACEs experienced by children, the higher the risks of immediate and future negative outcomes. The presence of adverse social conditions and historical trauma also increase risks and lead to intergenerational impacts. (See Figure 4 Pyramid of ACEs Context and Impacts.)

But the news is not all bad. Resilience, inherent in all of us and strengthened through healthy brain development, helps with the management of stress. There is something that can be done to ameliorate the negative impact of ACEs: negative experiences can be reduced, resilience strengthened and positive supports provided. (See Figure 5, Resilience Scale.)

While the biggest potential impact of toxic stress is on the brains of young children and adolescents, adults (especially those who themselves have experienced multiple ACEs) continue to be undermined by toxic stress experienced in adulthood. Their resilience can also be strengthened, albeit not as easily as the resilience of children and youth. With a non-stressful environment and the right supports, adults who have themselves experienced ACEs can provide the necessary stability to their children when those children are experiencing adversity, so that the stress is not toxic and the child’s resilience is strengthened rather than undermined.

Figure 3: Adverse Childhood Experiences

Figure 4: Pyramid of ACEs context and impacts

How does this play out in the family justice system?

Differences among family members are inevitable, and are not necessarily harmful to children. Experiencing some level of stress is what strengthens children’s resilience. If the differences are managed well within the family, children develop the capacity to manage conflict well as adults.

It is when families are having difficulties managing differences that they often come into contact with the family justice system. Families facing family justice issues related to separation and divorce, such as, neglect and abuse and family dysfunction, including mental health and substance abuse, violence and incarceration (all designated as ACEs) will likely be experiencing heightened stress that could be or become toxic.

The family justice system is intended to help families resolve disputes about their family justice issues. In practice, however, the system often exacerbates the stress families are already experiencing, thereby increasing the likelihood that the stress will become toxic.

This is, in part, because the family justice system is based on an adversarial dispute resolution model. In this model, the justice system’s role is to provide a neutral third-party decision-making process for unresolved disputes. The adversarial model assumes that the best way for that neutral third party to make just decisions is in a court process that regulates a clash between opposing forces. It is presumed that out of this clash will emerge justice.

While the system may see itself as playing the benign role of helping to resolve disputes, the adversarial approach creates a win/lose narrative that fuels, rather than diffusing, the toxic stress that may be at play in the conflict between the adults in the family. From the perspective of the participating adversaries, the system encourages them to dredge out the most negative aspect of the other, assume the worst at each stage, confront the other, and work towards an end goal of overcoming the other. Rather than creating optimum conditions for an environment that supports healthy brain development in children, it increases the toxic stress and risks serious immediate, long-term and intergenerational negative health effects on both children and adults.

What is the family justice system’s role in promoting family well-being?

“To be entirely or even mainly focused on the resolution of disputes in our pursuit of justice is, I submit, to miss much that we should expect of our legal systems. A broader view is needed.”

- Richard Susskind, Online Courts and the Future of the Justice System, p. 66

Richard Susskind argues that the concept of access to justice should embrace four elements:

- Dispute resolution – an authoritative forum for the vindication of people’s legal rights

- Dispute containment – nipping disputes in the bud or providing justice system responses that are proportionate to what is at stake and in the best interests of litigants

- Dispute avoidance - building a fence at the top of the cliff, rather than focusing on how responsive and well-equipped the ambulance is at the bottom

- Legal health promotion – empowering people to access the many benefits that the law can confer.

We can deduce from the brain science that adversarial dispute resolution processes, designed as clashes between the participants, should, as much as possible, be avoided to the benefit of all family members, particularly the children. A family justice system focused on family wellbeing will lead to designing a system that creates the conditions for de-escalation of conflict, and puts a premium on the dispute containment and avoidance roles of the family justice system. This might mean using the authority of judges to divert cases out of the justice system entirely, or creating a presumption of consensual dispute resolution (including mediation and Collaborative Practice, such as is currently being tested by the BC Provincial Court in Victoria, and soon Surrey), or working upstream to avoid court entirely.

Promoting legal health includes empowering family members to manage their own conflicts and to live a good life, in accordance with their rights as humans, as Indigenous peoples or as children. This might mean providing separating parents easy access to online co-parenting tools or child support calculators, or involving Elders in decisions about the children from their communities, or giving children and youth the safe opportunity to participate in decisions that impact them, and thereby allowing them to realize their rights under the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child.

Focusing the family justice system on family well-being and taking a broader view of access to justice will lead to policies and programs that we have only begun to imagine.

Working in partnership with other sectors

From the perspective of the family (adults, youth and children), family legal issues are most often secondary to social, relationship, parenting and financial issues. Making family well-being the focus of the family justice system leads to recognizing that the justice sector is not where the solutions lie for most families. The authority of the court may still be needed to combat power abuses within families, but issues that require skills, knowledge and experience not held by judges and lawyers can and should be referred to others outside the justice system.

A transformed family justice system focused on family well-being will support and be supported by professionals from other sectors, and all will be aligned around the common goal of child and family well-being. The justice sector will be integrated with the health (particularly mental health), education and social services sectors, allowing lawyers, judges and mediators to do what they do best, but not in a silo that plays down the non-legal issues of families.

The shift in focus to family well-being is not intended to turn lawyers and judges into social workers or mental health professionals. Instead, it will lead to the justice system working alongside other societal systems, and together with them, supporting families to achieve wellbeing by offering its particular contribution to that goal.

While the health and social services sectors may be seen as the more obvious leads in generally promoting family well-being, it is up to the justice system to take the lead in designing justice sector policies and processes, and supporting innovations, that reduce toxic stress, strengthen resilience and get families the support they need as they work through multi-faceted issues that bring them into contact with the family justice system.

STATEMENT OF COMMITMENT

Adverse Childhood Experiences and the Family Justice System

Heightened parental conflict during separation negatively affects children, and increased anxiety reduces parents’ ability to support children through an inevitably stressful situation. Interaction with the court system too often exacerbates parental conflict and anxiety. Instead of supporting the natural resilience of children by giving them voice, the family justice system frequently leaves children feeling unheard and thus more vulnerable.

On October 30, 2019, the Access to Justice BC Leadership Group met to hear about the scientific research on Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs) and child resilience, and the evidence of immediate and long-term adverse impacts on children of parental conflict and anxiety during separation. This led to the conviction that action – both within the justice sector and across other sectors - is necessary, and to a commitment from Access to Justice BC to take leadership to address this issue. This will involve looking at the family justice system in a different way – from the perspective of families and children - and defining its success in terms of its positive impact on child well-being, and the extent to which it reduces, rather than exacerbates, parental conflict and anxiety.

The nature of this leadership will require further consideration to make it practical, impactful and consistent with the governance limitations of Access to Justice BC. Individual organizations are not being asked to endorse this Statement of Commitment, and collective leadership by Access to Justice BC (or the Leadership Group) does not bind any individual organization to a particular course of action or at all. This joint commitment is supported by the vast majority of the Leadership Group, but is not unanimous.

Opportunities to reduce parental conflict and anxiety and increase a child’s resilience will differ depending on the child and their family situation, community and culture. It is recognized that historically, by reason of state actions to separate Indigenous children from their parents, Indigenous children and adults in British Columbia have disproportionately been subjected to the inter-generational impacts of adverse childhood experiences, and that opportunities to address this sad reality lie within Indigenous communities and culture. Still justice system leaders have a supportive role to play.

Therefore, the Access to Justice BC Leadership Group:

- Commits to addressing the adverse impact on children of parental conflict and anxiety during separation;

- Confirms the Action Framework set out below; and

- Agrees to the development of a practical plan for cross-sector/cross-sectoral leadership to be brought back to the Leadership Group in the spring of 2020.

ACTION FRAMEWORK TO ADDRESS ADVERSE IMPACT ON CHILDREN OF PARENTAL CONFLICT AND ANXIETY DURING SEPARATION

Goal: Increased well-being of children experiencing parental separation.

Vision: A family justice system designed to reduce parental anxiety and conflict, and enhance children’s resilience

Obligation: UN Declaration of the Rights of Children, Rule 1-3 of the Supreme Court Family Rules, Rule 1 of the Provincial Court (Family) Rules and section 37 of the Family Law Act

Guiding Principles: (Adapted from Meaningful Change for Family Justice: Beyond Wise Words):

- Minimize conflict - Programs, services and procedures are designed to minimize and reduce the extent and duration of conflict and its negative impact on children.

- Collaboration - Programs, services and procedures encourage collaboration and consensual dispute resolution is at the centre of the family justice system, provided that judicial determination is readily available and accessible when needed.

- Client Centred - The family justice system is designed for, and around the needs of the families that use it and the children who are affected by it.

- Empowered families - Families are, to the extent possible, empowered to assume responsibility for their own outcomes.

- Integrated multidisciplinary services - Services to families going through separation and divorce are coordinated, integrated and multidisciplinary.

- Early resolution - Information and services are available early in disputes to help people resolve their problems as quickly as possible as is appropriate to the dispute and the emotional circumstances of the parties.

- Voice, fairness and safety - People with family justice problems have the opportunity to be heard and the services and processes offered to them are respectful, fair and safe. Children have the opportunity to have their views and preferences heard.

- Accessible - The family justice system is affordable, understandable and timely.

- Proportional - Processes and services are proportional to the interests of any child affected, the importance of the issue, and the complexity of the case.

Approach: collaborative (including multi-disciplinary), user-centred, experimental, evidencedbased and applying an Indigenous lens.

Primary objectives:

- Increasing parental capacity

- Enhancing children’s resilience

- Designing the justice system to reduce parental conflict and anxiety, and enhance children’s resilience.

This Framework links to the Access to Justice Triple Aim in that it seeks to improve access to

justice at the population level and the experience of children and families with the family

justice system, and to do so in a way in which the costs are proportional to the benefits.

| First Name | Last Name | Title | Affiliation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Robert | Lapper QC (Chair) | Lam Chair in Law and Public Policy | University of Victoria |

| Nancy | Carter | Executive Director of Family Policy, Legislation and Transformation | Ministry of Attorney General |

| Sahara | Davis | Member | Youth Voices Leadership Team |

| Eileen | Janel | Senior Project Coordinator | Joint Collaborative Committees of Doctors of BC and the Provincial Ministry of Health |

| Jennifer | Muller | District Counsellor, North Vancouver School District | Public |

| Wayne | Plenart | Family Law Lawyer & Mediator | Justice Sector Educator |

| George | Psiharis | Chief Operating Officer | CLIO (Cloud-Based Legal Technology) |

| Kerry | Simmons QC | Executive Director | Canadian Bar Association BC, Family Law Lawyers |

| Dr. Shirley | Sze | Chair | Child and Youth Mental Health and Substance Use (CYMHSU) Community of Practice’s ACEs Working Group |

| Kaitlyn | Chewka | Volunteer | Access to Justice BC |

| Nika | Robinson | Volunteer | Access to Justice BC |

| Jane | Morley QC (support) | Strategic Coordinator | Access to Justice BC |